miyazaki's ugliest creatures are his most important

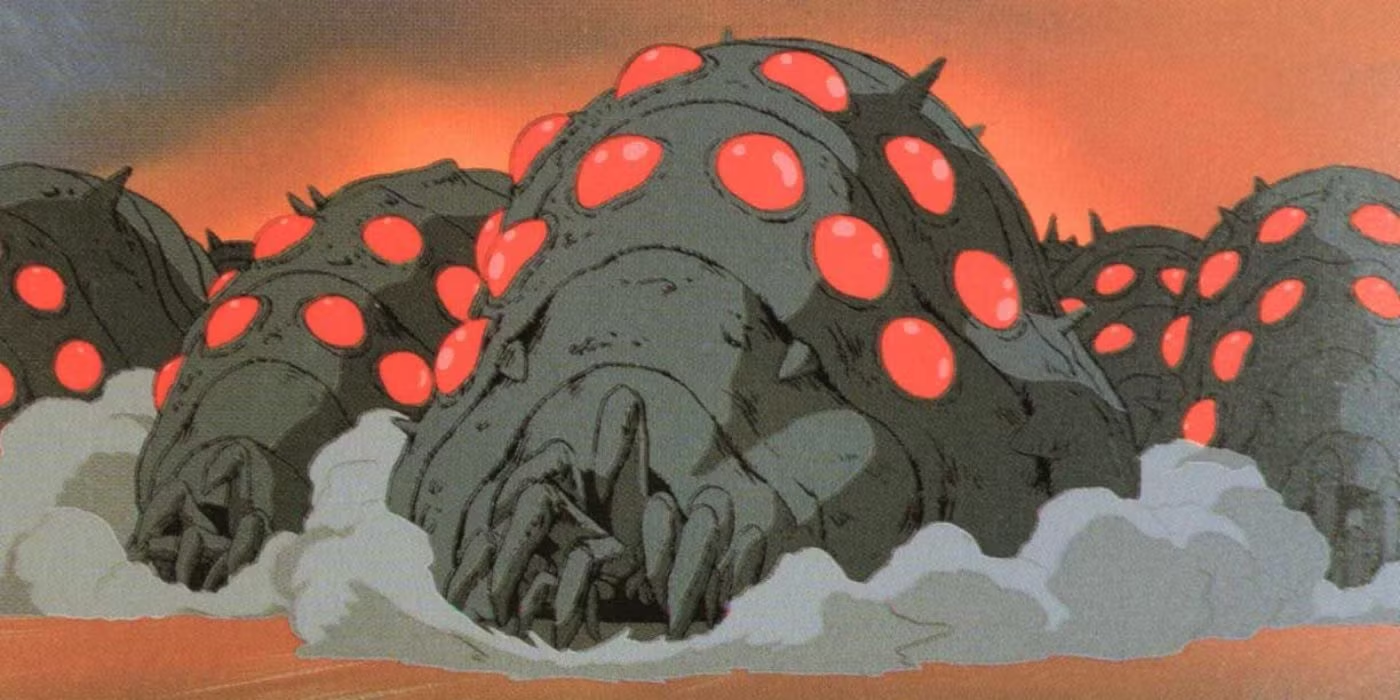

the Ohmu are ugly, and that's the point.

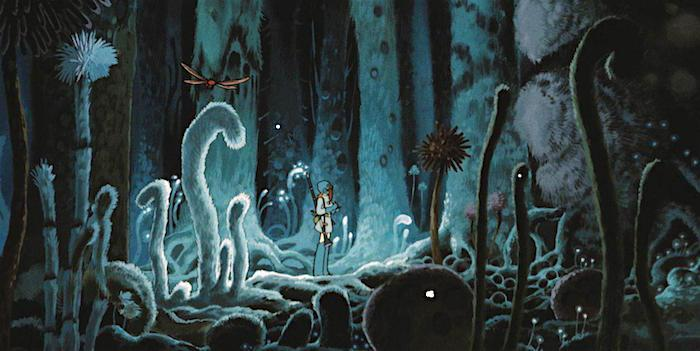

I recently rewatched Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. The story takes place a thousand years after a devastating human war, and there's a rapidly spreading jungle that's toxic to humans.

One of the creatures that lives in this poisonous forest is the Ohmu — a massive, insect-like thing that's hundreds of times bigger than humans and looks like someone crossed a pill bug with a tank. They're honestly terrifying, and a lot of the human characters in the movie fear them, as well as the many other insect species that find their home in the toxic jungle.

While some aspects of nature — like bears, whales, or birds — are pretty easy to anthropomorphize and connect with as humans, Ohmu decidedly resist such familiar framing. The film's director, Hayao Miyazaki of Studio Ghibli, designed them to be so fundamentally other than humans that our usual ways of connecting just don't work … and that's exactly the point.

Miyazaki doesn't try to make the Ohmu relatable or cute, but the title character in the story, Nausicaä approaches them with curiosity instead of fear, and treats them as beings worth knowing rather than problems to solve. She sees value in them not because of what they offer humans, but because they exist. Through her eyes, we as viewers start to see the Ohmu differently: less like monsters, and more like ancient, powerful guardians doing work that matters beyond human understanding.

(Btw, a lot of my thoughts here were sparked by this excellent video essay that I first watched a few years ago. It's definitely worth checking out.)

The "ugly" creatures we dismiss

Many insects in our world get dismissed as ugly, scary, or pests — creatures not worth our attention because we don't perceive them as "useful" to human interests. Yes, insects perform crucial ecological functions: pollinating flowers, breaking down and returning nutrients to ecosystems, sustaining countless animals as food, and more.

But framing their value in terms of human utility misses something essential. Even if they weren't fulfilling these roles, even if they weren't "useful" in some measurable way ... they would still be worth protecting. Their existence alone gives them worth.

The numbers are stark: insect populations worldwide have decreased by approximately 45% in just four decades, and we're continuing to lose about 1–2.5% of insect biomass annually. This is a pretty significant collapse of intricate networks that are having and will have rippling impacts on global ecosystems.

Nature thrives without human approval

Here on Earth, pollution, deforestation, mining, war, and genocide have harmed both human and non-human life for generations. There are years of harm for both planet and people to heal.

In Nausicaä's story, we learn that the toxic jungle came about because of the years of war that poisoned the land. When the spores are grown in clean soil and water, they're totally harmless to humans.

That said, we also learn that the jungle is only "toxic" by human standards. A complex ecosystem — namely, the Ohmu and other insects and creatures — adapted to and learned to thrive in apparent decay. The forest exists on its own terms, not those of the humans. There's remarkable beauty in the relationship between life and death, growth and decomposition — beauty that exists whether humans witness it or not.

Our world on Earth contains these same relationships, many occurring at scales too small for human eyes. And the better we understand these intricate networks, the better we can find our rightful place within them.

We see in Nausicaä's story and in our world repeatedly that nature can be destructive, terrifying, and very capable of devastating human communities … especially when we fail to respect it. While humans have responsibility to steward the Earth, we can't (and shouldn't try to) control nature. Instead, we should pay closer attention to and deepen our relationships with the natural world — even with what we perceive as ugly, frightening, or useless.

Creatures don't need to prove their worth

The revolutionary act isn't learning to see insects as beneficial to humans. It's recognizing that they don't need our approval to have worth.

A question I see frequently coming up in conversations about our current environmental crisis: if nature is resilient enough to survive and eventually thrive without humans, why does our action matter now? After all, the Earth has recovered from mass extinctions before.

But this view misses something crucial that Miyazaki understood when he created Nausicaä's world, and something that's been present in Indigenous knowledge and histories for time immemorial. Humans are not separate from nature and trying to save it from the outside; we are nature. When we work toward environmental health, we're working toward our own safety, well-being, and justice too.

The communities most affected by environmental degradation — whether that's air pollution, climate-exacerbated disasters, toxic waste streams — are often the same communities already facing systemic oppression. Environmental justice and human justice aren't separate causes.

Humans are part of nature

Humans also can and do belong within an ecosystem. Not as controllers, but as participants. When we fight for the survival of "ugly" insects or defend habitats that seem useless, we're really fighting for a world where all kinds of living things can exist without having to prove their "worth" first.

As Hayao Miyazaki said: "Human beings are part of nature, are the ones who have destroyed nature, and are the ones who live within the nature they have destroyed."

Nature possesses intrinsic value. The Ohmu appear "ugly" only because they resist our instinct to make everything familiar and relatable. (Though, at the end of all of this, I will admit that I've really come to find these giant weirdos pretty adorable.)

The bugs and other weird and wonderful creatures of our world deserve our attention — not just for ensuring human survival on this planet, but primarily because they exist, have always existed, and carry on their essential roles in the ecosystem regardless of whether we're watching and assigning it value.

And in the same way, you're worthy, too.

P.S. If you're a paid supporter of Filter Feeder, expect an illustrated zine about this topic in your mailbox soon!