frogs have always been perfect

& they’ll continue to be for millions of years (if we take good care of them)

This is the pumpkin toadlet. It’s less than an inch long. Behold:

They’re so incredibly tiny that their bodies’ balancing mechanisms are too small to function the same way other vertebrates’ do (see this article for more on how minuscule inner ears make it tough for this lineage of frog to sense body orientation).

Thankfully, it turns out that not sticking the landing is okay for these frogs — being so teeny means that their biggest concern when it comes to predators is just getting away, no matter what (poor) form that takes.

“They’re not jumping around a lot, and when they do, they’re probably not that worried about landing, because they’re doing it out of desperation,” study co-author Edward Stanley. “They get more benefits from being small than they lose from their inability to stick a landing.”

I’ve also seen some speculation about whether their stiff landings are meant to mimic falling foliage to further hide from predators, though I haven’t seen any specific sources to back it up at this point. Any frog-experts out there, please let me know if you have thoughts on this.

Frogs weren’t always jumpers (and clearly some still … kinda aren’t). This raised many questions for me. How’d the “modern frog” as we know it come to be? Why did some frogs, like the pumpkin toadlet, evolve to be so itty bitty? How tiny could their lil’ eggs possibly be? (Update, they typically hatch in groups of at most five.) Have frogs always laid eggs in water? Do all frogs come from tadpoles? Why aren’t there frogs in the ocean???

The ancient amphibians that started it all

It’s swampy, it’s full of giant insects … it’s the Carboniferous Period, which began a little over 350 million years ago and is, very fittingly (a la giant insect) also sometimes called the Age of Amphibians.

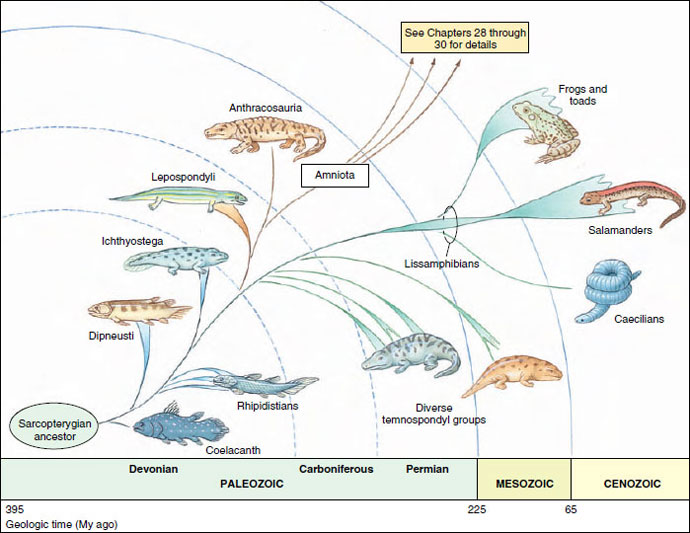

Much like humans, amphibians are descendants of tetrapods, with “tetra” being “four” and “pod” being “feet.” Tetrapods as we know them officially began after the internet’s favorite fish-tetrapod in-between, Tiktaalik. We’ll skip a little ahead in time for the sake of frogs, but in case you’re still thinking about fishapods (me too), here’s a great, recent PBS Eons video for ya.

That branch in the image below titled “lissamphibians” marks the rise of amphibians as we know them today. The big three of these modern lissamphibians are frogs (which includes toads), salamanders (which includes newts), and caecilians (which are, contrary to being lengthy and legless, NOT a direct snake-relative).

There are several groups of ancient amphibians, but Temnospondyls kinda steal the show for me. They also have a Dinopedia page. This video does a good job of outlining what makes these amphibian ancestors so special:

Weird heads, tiny bodies, & endless possibilities

In some ways, frogs have kept close to their ancestors over the years with their scaleless skin and need to lay eggs in water (most of the time — we’ll get to this shortly). But in other ways, frogs as we know them today are so far differentiated from the giant amphibians that once walked the Earth.

Weird skulls are both a similarity and a difference. This article shows off some of the extreme heads that modern frogs have evolved (and turns out, some of those head shapes mirror ancient frog ancestors for reasons still being uncovered).

“Weirdly, it’s easier for us to generate beautiful images of skulls than it is to know what these frogs eat,” Blackburn said. “Natural history remains quite hard. Just because we know things exist doesn’t mean we know anything about them.”

Also, ancient amphibians didn’t really jump. Modern frogs evolved a unique leg structure and pelvic joint that scientists suspect help with their jumping abilities (both in power and accuracy), yes — but while the toadlet has power, it falters in accuracy.

What the heck happened that made magnificent giant amphibians evolve into teeny, clumsy toadlets? The Mini genus of frogs (a very apt name) gives a little insight into this:

The Mini frogs likely adapted in order to take advantage of ecological niches inaccessible to larger creatures; the amphibians, for example, might now be better equipped to hunt down tiny prey such as ants and termites.

In other words, frogs big and small each have their unique place in the world. But to return to another great article about the pumpkin toadlet:

It’s true that, in botching their landings, they’ve largely eschewed what most people might assume makes a frog fundamentally frog. But maybe the true marvel is that the toadlets have figured out a way to live without the signature hoppity-hop, all while embodying one of life’s extremes. The frogs may represent some of the tiniest amphibians that nature has ever, and will ever, produce; any littler, and there’d basically be no vestibular system at all. “It’s very possible,” Pie said, “that you can’t get a functioning frog smaller than that.”

So, tetrapods and tiny frogs in mind, the big question as we delve further into frogs of the present day is this: What defines a frog?

What is FROG?

First off, they’re like, almost everywhere. Frogs live in rivers, lakes, streams, trees, forests, underground, in water pools that form in flowers, and more. The only places they’re not typically seen are Antarctica and oceans. And even then, scientists found fossil records of frogs in a past Antarctica, and there are some frog species that can be acclimated to 75% seawater if necessary.

Second, they can breathe through their skin. Weird, but cool. (This is also why it’s tough for them to live in the ocean — saltwater and porous skin aren’t a very good mix.)

Third, the whole metamorphosis thing. Frogs lay eggs, eggs become tadpoles, tadpoles become frogs. EXCEPT NOT ALL FROGS COME FROM TADPOLES (yeah, all caps because I was floored when I learned this for the first time). The frog metamorphosis cycle is incredible in itself because there’s just a small number of vertebrates today that go through such intense metamorphosis, of course, but frogs have some incredibly wacky and wonderful ways of growing. Not all frogs lay their eggs in water, and not all of those eggs have a tadpole stage. Personal favorites include foam eggs, leaf eggs, and skipping the tadpole stage altogether. And I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the eggs-on-back strategy (beware on this one for anyone with trypophobia).

In the end, what I’m trying to say here (as someone *deeply unqualified* to speak definitively to the taxonomic boundaries of frogs) is this:

Each of the many thousands of species of frogs described today represent a little piece of evolutionary history in how they’ve carved out a place for themselves in the world. Many frogs today are struggling, but there are also humans working really hard to help them survive and adapt to a rapidly changing world. From ancient amphibians to the jumpers (and non-jumpers) we know today to whatever they may evolve into years down the line, frogs will never not be a boundless surprise.

Thanks for joining me for the first installment of this (honestly ridiculous) frogtober journey. See you next week with more celebratory content, and until then please enjoy this video essay on Frog & Toad. Frogs 4ev!